Carry that weight. (In a well fitting rucksack.)

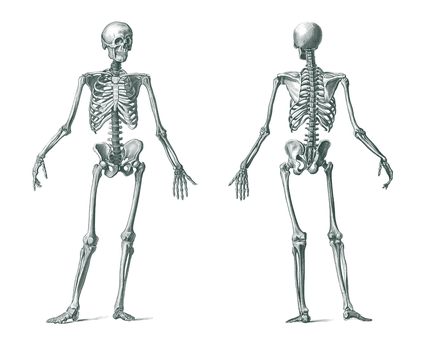

The above is a diagram of a human back, which can easily be viewed as a marvel of evolutionary engineering. An S-shaped spinal column surrounding and protecting our essential nerves cushions shock from ground impact to the brain.

The spine prevents our posture from resembling that of a slug and allows us to twist and flex in three dimensions. It is, by any measure a very useful thing to be in possession of.

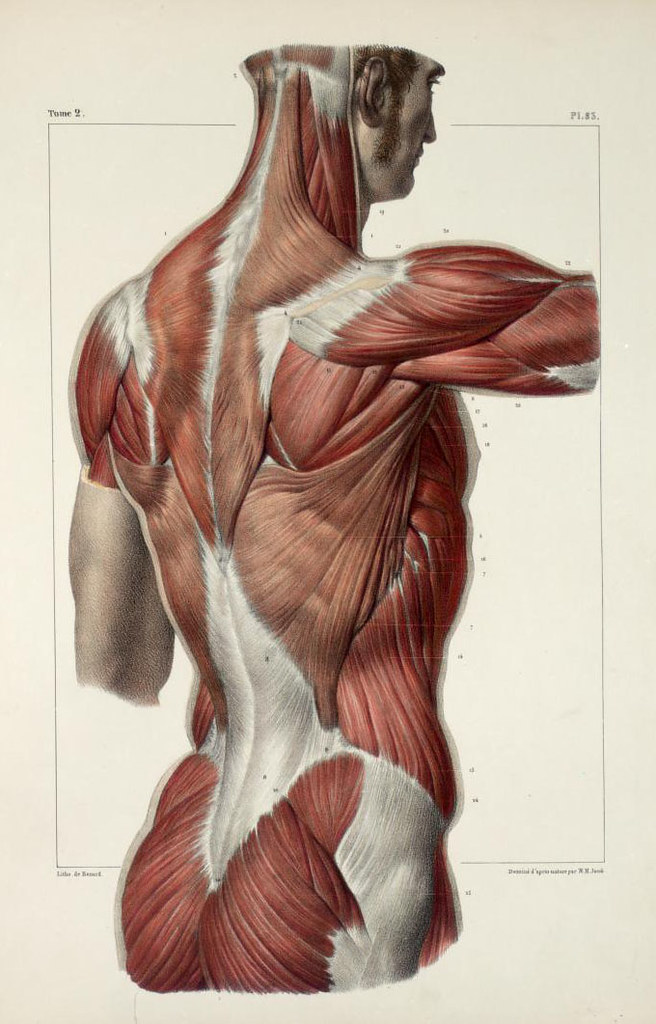

From a backpacker’s point of view though this biological structure makes for a pretty poor load carrying system. Any weight carried on the shoulders is ultimately transferred to the muscles of the lower back and if they tire, as they certainly will during a long mountain trek involving days of load carrying and minimal rest then they will function less well.

Any significant reduction in proper function will start to have an effect on posture, gait and health. Over time this will increase the possibility of a repetitive injury or a more traumatic incident if fatigue causes a loss of stability or poor adaption on rough terrain.

The problem is that our ability to flex and move comes at the cost of skeletal support. The lower back, as can clearly be seen has no solid support structure, no scaffolding if you like. Intertwined bands of muscle work together to maintain core stability and facilitate movement. Once these muscle groups fatigue their ability to maintain this stability is impaired, sometimes to the point of injury.

The solution is for rucksacks to be designed so that they bypass the lower back muscles and transfer the load from the shoulders as directly as possible to the hips. Allowing the legs to carry the extra weight comes with no downside or extra effort.

Our lower limbs are better at supporting loads because unlike the back they do have a rigid bone structure to back up the muscles.

The legs are so good at bearing loads that they carry our body weight around, day in day out and we barely notice. After a long day we get up the next morning and our legs are ready to go again.

This is true even after more extreme events such as marathons. Despite the muscles being very fatigued we can still walk, albeit gingerly and continue with everyday life. The femur and tibia connect the hip to the foot and this bony support structure allows us to function even when our muscles are a long way from peak performance.

Backpack fit.

Large backpacks are essentially a semi-rigid frame connected to a harness around the shoulders that then runs down the length of the back and attaches to the hips.

The length of the frame is critical. Too short and the hip belt becomes a waist belt and all the weight is borne by the shoulders and lower back. Too long and the hip belt sits around the thighs getting in the way of a normal gait and, once again leaving all the weight to be borne by the shoulders and lower back.

Only when the hip belt sits on the bony, sticky-out bit of the pelvis, or Iliac crest will the load be properly transferred to the legs. The problem is that humans are a complete nuisance and come in all shapes and sizes so there is no back length that suits all users.

This gives us two options; one is to try lots of packs to hopefully find one that is close enough to your personal back length to work properly or get one fitted to suit.

Once upon a time some manufacturers would produce large packs in S-M-L back length options. Berghaus even went as far as producing a fairly scary looking metal measuring frame to help shop staff guide you to the best size for you.

One problem was that the smaller back length meant a smaller capacity rucksack which wasn’t always made clear in the labelling. For years though this was as accurate as it got; good but still not ideal.

The system of multiple back options has now been superseded by rucksacks that feature easily adjustable back lengths. Karrimor and Lowe Alpine were among the first to market with their versions and the concept caught on so well that almost nobody produces expedition sized packs without some form of length adjustment nowadays.

These all involve a fixed hip belt and a shoulder harness that can be moved up and down to suit the human better. Some slide on rails, others are threaded through a ladder system and some are anchored in place using Velcro pads. Some are simpler to adjust than others but all of them work.

Manufacturers prefer adjustable harnesses over multiple back lengths because they only have to produce one version of a model and so tooling and production costs are reduced.

Users prefer the result because for most trekkers the size is more precise and a better fit ultimately should lead to greater comfort over time as the miles go by.

A common style of adjustable harness.

If you are comparing the comfort of two different packs then both should be adjusted to suit you, so that you are genuinely comparing like with like.

All back length adjustment should be done with a weighted pack. Empty rucksacks always feel great and they will sit too high for meaningful comparison to be made. Five to ten kilos of random stuff inside will give a much more realistic impression of how a bag carries and how well it fits.

Once you have the pack loosely on your shoulders the first thing to do is to tighten up the hip belt. It should wrap around the bony part of the hip. Now tighten all the other straps and wander around for a few minutes. If in doubt move the harness up or down a bit and see if the effect is positive or not. Repeat the process with another pack if you want to compare the way they feel.

If you are a man with a short back length then try a women’s pack as the range of adjustment tends toward shorter. Similarly, a woman with a longer back length may get on better with the range available on a men’s rucksack.

The goal is comfort so don’t be afraid to experiment to find what suits you. You’ll only regret it on the trail if you don’t.

Enjoy your hike.